Running bigger experiments is better than internal replication of smaller experiments

TLDR: Internal replication of experiments (repeatedly running the same experiment within a lab) is unnecessary and wasteful, if your experiments are well designed to start with.

External replication (later replication of ideas or experiments by different people in different contexts) is not discussed here.

This draft is long and needs some attention but I thought it was still valuable to post because there are some important ideas here. Any suggestions or comments welcome.

Introduction

At the end of a long conversation on the importance of experimental design and why nobody likes talking to statisticians, a colleague finally dismissed the possibility of erroneous findings with “..but of course, we always repeat all our experiments three times anyway.” Up until now, in the interests of collegiality and to avoid being considered a troublemaker, I’ve let these sorts of provocations slide. But this was the third time in as many weeks that experiments in triplicate had been presented to me as obviously necessary despite having no apparent statistical basis.

Online searches revealed that ‘why do biologists replicate everything three times?’ is a question occasionally asked by newcomers to the field but never satisfactorily answered, and revealed a lot of confusion about the role of technical replicates, biological replicates, internal vs external replicates of experiments, when each is necessary and what each is for. Peer-reviewed literature, grey literature and textbooks seem also to be fairly quiet on the topic of this ‘internal’ replication, despite its (apparent?) widespread use.

In honesty it’s been a while since I thought about this, but I was recently motivated to revisit this topic by the MRC guidance for the design of animal experiments in funding applications, which states:

[we require] an indication of the number of independent replications of each experiment to be performed with the objective of minimising the likelihood of spurious non replicable results. If there are no plans for studies to be independently replicated within the current proposal then this will need to be justified.

It’s not completely clear what the MRC mean by this, but if you want to argue against running repeats of experiments (and perform single better larger experiments instead) then this essay might help you with your justification. Below I explore some of the statistical implications of this strategy for error control, compared to a (more conventional?) approach of using a single larger (possibly blocked) experiment, and discuss what this reveals about how statisticians and biologists think about what scientific experiments can ever actually tell us.

Specifically, I discuss a strategy whereby a researcher repeats their experiment three times, and then considers a finding to have been demonstrated (positive or negative) if two of the three agree. I’ll call this the ‘2 of 3’ strategy.

Face validity

On the face of it, replicating an experiment three times does seem like reasonable mitigation against the false positive or false negative arising from a single trial.

That is, if something does work on at least two out of three occasions, wouldn’t you be reasonably sure that it was going to work again or at least was reflecting an underlying biological truth? Whereas if your experiment failed at least two times out of three wouldn’t you think it likely that the anomalous positive was the result of some fluke or technical error?

Well yes, and no.

False positives or negatives due to biases or natural variation are inevitable, and are exactly what good experimental design and analysis are there to control. And if experiment 1 still does go wrong in an unknowable and uncontrollable way, surely there’s a good chance that experiments 2 and 3 will behave similarly? And if you are studying an effect that genuinely varies across subpopulations, or with time, place or the alignment of the stars, then you need to design and analyse your experiment accordingly.

But is there any actual harm in taking this approach, and what threshold for discovery are you in fact demanding of your experiments if you do this? This clearly needs some exploration; to understand what the statistical properties of this process of replication are, and how can we get the desired outcome (low error rates and good generalisability) in as efficient a way as possible.

The implications of repeating three times on error rates

So what are the implications of using your valuable time, energy and mice to repeat every experiment on three separate occasions, and then democratically deciding among the replicates which answer is the truth? Let’s work this out in a simple hypothetical case.

Suppose you consult your statistician (humour me) and plan a well designed experiment to test a null hypothesis (H0) against an alternative (H1) such that the experiment has a power of 80% at a size of 0.05 (that is, you determine statistical significance at p<0.05).

Then you run this experiment three times, and only accept the result as true (reject H0) if at least two of the three results agree. Let’s ignore for now the possibility that findings could be statistically significant but in opposite directions.

What are the error rates of this combined experimental procedure (the 2 of 3 strategy) as a whole?

Implications for power (or type 2 error rate)

First, let’s work out the power. This is probability of detecting an effect if that effect was in fact there (a true positive). Each individual experiment has, independently, a power of 80%. You need at least two of the three to show statistical significance.

The chance of this happening is the simple binomial probability:

\(0.8^3 + 3\times 0.8^2\times 0.2 = 0.896\)

So if H1 is true you have a 89.6% chance of getting a positive result using this procedure, corresponding to a Type 2 error rate of 10.4%. This is an improvement on the 20% type 2 error rate for the single trial with 80% power.

Implications for size

What about false positive rate? If there is no effect (H0 is true) and your size is 0.05, that is you require p<0.05 in each individual trial, then the chance of a false positive for your two in three procedure is again easy to find:

\(0.05^3 + 3×0.05^2×0.095 = 0.0075\)

So a less than 1% chance of a false positive if H0 is true!

So this looks great! With three repeats (using the 2 from 3 strategy) you have reduced the risk of a false positive (if no real effect) from 5% to 0.75%, and increased power from 80% to as good as 90%!

But this has come at a cost of needing three times as much resource.

Equivalent single experiment

Was it worth it? How big would a single well-designed experiment have to be to achieve the same power and size? If your initial goal had been to design an experiment with power of 89.6% and size of 0.0075, what sample size would have been needed?

We can find this using a power and sample size calculator. (R code available)

If we work out the effect size needed such that any given N (our original single trial sample size) yields a power of 80% and size of 0.05, and then require that for the same effect size we want a power of 89.6% and a size of 0.0075, then the ratio of the original N to the revised N will reflect how much extra sample size we need.

It turns out that this same improvement in error rates is achieved with almost exactly 2N samples.

So by running one well designed experiment with twice the sample size instead of using three repeats, you will achieve the same error control with two thirds of the time and material you would otherwise have needed.

Optional stopping

“But wait!” you retort. “I would obviously only conduct experiment 3 if experiments 1 and 2 were in conflict. So I will not often use all three repeats.”

This is a good point. We can work out the probability of you actually needing all three experiments, hence what your expected average gain would be by using a single larger experiment instead.

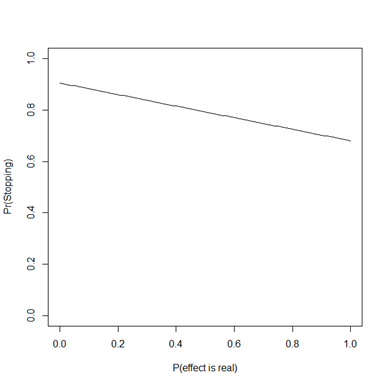

But we do need to introduce another parameter, the probability that your supposed effect is real (that is, H1 is true). For any such probability, the chance that your first two experiments agree is shown below:

So in all cases there’s actually a good chance (between 70% and 90%) that you’ll stop before needing the third trial. So the average cost of this 2 of 3 procedure is between 2.1 and 2.3 times N, the original sample size of each trial (so long as you stop after two trials that agree), compared with only 2.0 times N for running one large experiment. (Also, if we’re going to use optional stopping we can probably design a more efficient experiment in the first place).

So, all things considered, this isn’t an enormous improvement. In this case, where the original study was well designed, and if you stop after two trials with the same result then you’ll save roughly 10% of your resources by using a single larger experiment to get your error control rather than a strategy of 2 in 3 small experiments.

So in this case at least, using the 2 of 3 trials is a isn’t a terribly inefficient way to improve your Type 1 and Type 2 error rates. But the point does still stand that you get the same error rate control with 2N samples instead of needing the possibility of the third replicate, so long as you analyse them as one big experiment and not two smaller ones that may or may not agree.

Underpowered studies

All of the above supposed that the three individual independent experiments were each well designed to begin with. Suppose however that your initial experiment was underpowered, such that you only had a 50% chance of detecting a real effect at p<0.05.

In this underpowered case your 2 of 3 strategy yields a power of 0.5, so there is no increase in power at all. Your Type 1 error is still 0.0075 though, so you have still improved type 1 error control by running three reps. The equivalent single stage experiment would need to have a sample size of 1.9 times the size of a single trial to achieve this error control criteria, and the chance of stopping after 2 is between 0.9 and 0.5 (say 0.7) depending on the chance that your hypothesis is actually true.

So your expected cost for the 2 of 3 strategy is 2.3N, while your known cost for a single larger study with the same error control is 1.9N. So you would save about a 0.4N or roughly a fifth of your expected resource by using a single experiment rather than having a strategy of needing 2 in 3 internal reps to be significant.

If your experiment is even more poorly powered, say at 30%, then the power of the 2/3 strategy is 0.3^3 + 30.3^20.7 = 0.216. So you lose power compared to a single trial. To get the same effect with a single study you’d need 1.75*N samples. Your probability of stopping early is around 0.75 (between 0.6 and 0.9), even though in a lot of cases you’d stop erroneously if the alternative hypothesis was true. So here the saving is 2.25 - 1.75 = 0.5N; again that’s just over a fifth of your expected size under the 2/3 strategy.

Reporting

So far I have only discussed error rates and statistical significance. The question of how you might report experimental results when you’ve used internal replication is complex.

Clearly, only showing one trial (say the first one, or a ‘representative’ trial) is an inefficient use of data, hides data, and is unacceptable. Selecting a ‘significant’ trial to support a significant finding is biased, while risking selecting a ‘non-significant’ trial to reflect an overall significant result is non-sensical. It is clear that reporting all of the data from all of the trials you have conducted is the only correct way to proceed, along with a clear description of the process by which you decided to stop conducting more studies, but this would be messy and far more difficult to interpret than simply conducting and reporting a single experiment in the first place. In short, unbiased and efficient reporting is very difficult if you are using internal replication at the level of the experiment.

So why do we intuitively have more trust in a replicated experiment?

I have shown that running one big experiment is a better use of resources than two or three small ones, if the goal is to control false positive and false negative risk, and it seems obvious that a single large experiment is much easier to report than lots of small ones.

But casting aside the maths, at some human level I think that even would I intuitively have more faith in an idea if it is demonstrated more than once in small experiments, compared to being shown exactly once in a large experiment, even if that large experiment is statistically just as good as a set of small ones.

So what is going on? Can we model this (erroneous) thinking more formally to see where the problem lies?

My theory is as follows:

Scientists (perhaps people) don’t think about type 1 and type 2 error rates when designing, analysing or interpreting experiments. Nor do they typically see experiments as estimating some unknown population-level quantity. Instead, experiments are viewed as tests of whether an effect exists, reflected almost completely by the statistical significance of the outcome (that is whether the experiment worked or did not).

In a way this is natural, and our (wrong) notion of replicability reflects and reinforces this. The idea that if you replicate an experiment you should get the same result again and again is an intuitively attractive and often stated one, but it’s wrong. P-values are very unreliable. Two identical experiments can be perfectly consistent with each other even if they return very different p-values. In fact their results should always be different, because of the role of chance. (Replication results with p-values that are too similar are viewed with extreme suspicion by many).

Replicability does not mean that the same experiment repeated should generate the same qualitative result. It does mean that the estimates arising from them should be close enough together such that their difference is attributable to natural variation in the outcome measures.

For example, if an experiment has 50% power under a ‘true’ effect, then statistical significance under H1 is a coin toss. The ‘results’ of successive experiments will be random and completely independent of each other, yet this is no reason to consider them inconsistent.

But under this (bad) interpretation, it’s easy to see why seeing successive positive results from repeated experiments is more appealing than seeing one positive from a single large experiment. It’s also easy to see how this reinforces the idea that experiments are likely to randomly ‘fail’ for mysterious methodological reasons, as under this way of thinking there is no other way to account for experimental inconsistency.

So, suppose we believe that our experiments should ‘work’ if the idea underlying them is correct, they should ‘not work’ if it is not, and that any deviation from this is caused by methodological error (which occurs with unknown probability independently of the size of the study). Under this model getting one success from one trial tells us almost nothing. It could be an error; it could be a true discovery and we have no way of saying which. Yet if we see two out of three trials work, then we may start to believe the more parsimonious explanation that one out of the three is a false negative rather than two out of three being false positives, which strengthens our belief in the finding.

The central fault(s) in this reasoning is the failure to appreciate that:

All experiments have both type 1 and type 2 error rates,

these errors do not occur because the experiments are faulty but occur due to chance,

these will naturally lead to apparently inconsistent findings, particularly if studies are underpowered, and

large studies have smaller error rates, and are more reliable, such that we should update our beliefs by a greater amount based on larger studies compared to smaller ones.

I agree that errors due to methodological failures can and do occur. However, splitting resources across two or three smaller trials, each of which is analysed separately, (ie internal replication) does not remove any of the randomness or methodological issues present in the alternative larger study, but does inflate their ability to derail our interpretations.

Conversely there is nothing to suggest that that a bias built into in a single study wouldn’t also be present in a replicate. In fact you’d expect that it would be. Good experimental design, good monitoring, analysis using models that can account for this variation (or random human error) and an appreciation of the ‘estimation’ paradigm for analysis is the appropriate response to this challenge, not the ‘brute force’ and frankly illusory safety net of internal replication.

For example, if we believe in a day-to-day variation in results that leads us to want to replicate across different days, then we can design a single blocked experiment and conduct it over multiple days, such that any ‘day’ effect is balanced over treatment conditions and a day-by-treatment effect might be estimated.

Side notes and caveats

This is not to downplay the importance of biological replication. Biological replication is essential, and we should tend to emphasize biological replicates over technical replicates where possible. Where a source of variation exist, experiments should include replication across that source. But we should still always analyse our replicates together as part of a single experiment.

If we do want to retain the possibility of optional stopping, whereby we allow the possibility of getting more samples if uncertainty remains after an initial analysis, then we can, and I advocate this where appropriate, but it must be explicit in the original design, accounted for in analysis and acknowledged in the interpretation.

External independent replication of published findings is also important, adds generalisability, and, given the state of the published literature, is more crucial than ever. But the aims of external replication are very different to those of internal replication.

This does not apply to internal replication of computational pipelines, which I think is a good idea (advocated here https://www.bitss.org/internal-replication-another-tool-for-the-reproducibility-toolkit/)

Discussion

Drilling into the statistical properties of a strategy that relies on internal replication of experiments and the possible reasons for their intuitive appeal leads to clear practical suggestions and highlights some potential misunderstandings regarding the meaning of replicability and even the role of experiments and what should be inferred from them.

Summary:

A strategy of reporting an effect when two out of three independent trials rejects H0 at p<0.05 has an overall type 1 error of 0.0075 (ie is equiv. to a single experiment reporting at p<0.0075).

Whether the power of this strategy is greater or less than the power of each individual experiment depends on whether each individual study is adequately powered in the first place. If each study is underpowered then the chance of true positive with this strategy is very low, if each individual trial is well powered then it is high.

An alternative strategy of running a single larger trial with the same error rates has a smaller expected sample size required in all situations tested, typically between 10 and 25% less, and is more predictable with respect to the resources needed. Using the ‘2 in 3’ strategy risks wasting more than 50% additional time and resources in the case that the third trial is needed to arbitrate between apparent inconsistencies from the first two.

Good reporting of results from a single larger study is much easier than reporting based on a strategy of internal experimental repeats, and this uses available data much more efficiently.

Studies are not inconsistent just because one reports a statistically significant difference while the other does not. Consistency of study findings should be judged based on whether the difference between their estimates is commensurate with the precision of each estimate. It is simply impossible to judge this with p-values alone.

Major sources of misunderstanding are the over-reliance on ‘statistical significance’ as the summary statistic for experimental results, which does not permit us to give more weight to larger trials compared to smaller ones, and the failure to consider type 2 errors as a source of apparent inconsistency between trials.

Recommendations

Internal replication of studies with identical conditions should be discouraged, where these would have been used, larger studies with more ‘biological’ replicates and stricter thresholds for error control can instead be safely recommended. These larger studies should be well designed, a good starting point for design would be using the proposed smaller studies as blocks within the larger design.

Where replicates have been made, we must not report findings from ‘a representative’ experiment, but should instead pool data using an appropriate method for pooling such as a mixed effects model or meta-analysis.

Studies should be reported using estimates of differences along with the standard errors of differences or confidence intervals for differences, rather than relying on p-values.

Existing literature (todo - fix this and add more)

There isn’t much literature on the value or otherwise of internal replications of experiments. I have certainly never seen a publication that formally explores and advocates this.

This author has roughly the same view I do. https://www.cell.com/trends/plant-science/fulltext/S1360-1385(99)01439-9.

I couldn’t find anything on internal replication in the NC3RS website, except that the ARRIVE guidelines for reporting (rightly) insist that it is described when it was done.

For good introductory reading on types of replication and how to design and analyse studies with replicates appropriately, I would recommend Lazic (2016) Experimental Design for Laboratory Biologists.

Recently with the ‘replication crisis’ there has been an instinctive reaction to do more internal replication in psychology. A blog post and an article show theoretically and empirically that this is not helpful.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.3758/s13423-016-1030-9

There is a lot written more generally about the importance of replication in science.

https://www.aje.com/arc/why-is-replication-in-research-important/